Below are the introductory comments given by Dr Johnston McMaster at the BEING CHRISTIAN TOGETHER: Conference on local inter–church engagement held in June.

This event was co–sponsored by the Irish School of Ecumenics (with the support of the Community Relations Council NI) and the Irish Inter–Church Meeting and brought together seventy participants from across the island of Ireland for a networking conference to encourage and support local inter–church engagement.

Where In The World Are We?

We Are Living With the End of Christendom

This does not mean the end of faith but the end of a religio–political system that began in the 4th century, lasted in Europe for 1500–1600 years and was generally bad for religion and for politics. In 313CE with the Edict of Milan, Emperor Constantine Christianized the empire, the church got into bed with the state, the state sponsored the church and clergy, the church legitimised the state’s wars and blessed it’s armies. Towards the end of the 4th century, Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the only legal religion. The church was now very close to political power which meant it shared the corruption of power. Christendom was beginning to shake at the foundations by the 16th century and it was at the beginning of the 20th century that the catastrophe of WWI killed Christendom. The church in the West lost its power, privilege and status and is now no longer a domination system, experiencing also the loss of public influence and numbers. If we look at the Irish decade of events 100 years ago, that shaped the Ireland we live in today, we see then very powerful churches, controlling and wielding enormous authority. None of that exists today. Irish churches have been culturally disestablished and depriviliged. We are struggling with that and have hardly acknowledged the death of Christendom.

We Are Living Through The Reality Of The Secular

Some months ago I found a one page manuscript on my desk. I didn’t know where it came from, I suspect it fell from a reference book I had been using. It was the script of a broadcast I did 37 years ago. I read it and thought it was good! I read it again and thought the concluding paragraph I would never use now. The language was too theological and religious. Today the majority of listeners in Northern Ireland would not make any sense of it. Society has changed so much. We are all secular now. Churches complain about being marginalised. Leaving aside the aggressive and intolerant secularism, secular is something different. Secular is the separation of Church and State. We are no longer in bed together and the churches can’t dominate, control, determine legislation. Secular is also pluralist democracy, the many and the diverse. In a pluralist democracy all voices have the right to be heard and no one voice is privileged. Power is dispersed and shared and the churches are having difficulty getting used to that. There is still a role and a voice but no longer privileged. We are having to work out a very different relationship between faith and politics, church and state. And the secular is here to stay.

We Are Living In a Time of Political Uncertainty And Brokenness

When we elect politicians we give them a mandate to govern and legislate. For nearly three years now in Northern Ireland that mandate has been ignored. We have had no governance and no legislation, and as democratic citizens we have been unbelievably passive about it. And we have the chaos of Brexit which has exposed the brokenness of politics in the UK. The model of parliamentary democracy is not working and wasn’t working long before the Brexit referendum. Brexit has also exposed the reality of a disunited Kingdom, largely because of a failure to recognise that the UK is made up of very diverse regions, each of which is different with different needs and identities. The concept of the UK has been essentially England and being British is an invented fiction. Brexit is also the revenge of colonial nostalgia. The next two decades, even the next decade may well see a series of constitutional crises, of which Northern Ireland will only be one. People of faith will not be able to sit above or outside of this turmoil. Our identities, loyalties, hopes, aspirations and fears will all be in the mix and this will challenge the depth and reality of our faith and our ecumenical and community relations. We need to be engaged in some deep, civic, theological and political conversations, conversations together.

We Are Already Got Up In the Vortex of Identity Politics

We all have multiple identities, always more diverse and complex that we think. In a sectarian society we are always being squeezed into the straitjacket of Protestant or Catholic, Unionist or Nationalist, men or women, straight or gay, indeed a range of binary identities or dualisms. We are in a world now, even in small Northern Ireland where all of these identity markers are up in the air. Identities are in a state of flu, settledness and certainties are breaking down and this is where fear, rigid moralism and religious and political fundamentalism can triumph, and violence can emerge.

I have been involved with a colleague on an extensive educational programme, Liberation From Patriarchy For Gender Justice, rolled out in Derry, Strabane and Donegal. It is funded by Peace IV, the European Peace and Reconciliation fund. There are all sorts of criteria to be met. Courses have to have a certain percentage of Catholics and Protestants. From two large courses the majority of participants have identified as neither Protestant nor Catholic. They do not identify as either and there are growing numbers of people in Northern Ireland who do not want to be identified as either Catholic or Protestant. There are also growing numbers who refuse the identity markers of Unionist or Nationalist. And there is a whole bewildering spectrum of gender identities, given some expression as LGBTI. Identity politics are radically shifting and it’s all complex. In the flux of shifting identity people of faith can’t pretend it’s not happening, still less take flight, but engage together beyond tribal identities to shape a new anthropology, the primary identity of what it means to be human and to be human together. We might describe this as shaping a theological humanism.

We Are Confronted With Major Global Challenges

It is in the face of these challenges that we feel most overwhelmed. Two major challenges, locally and globally are climate change and unregulated capitalism. Global emissions and the financial crisis are linked. We are aware now of the apocalyptic reality of climate change but seem paralysed about doing something. ‘What is really preventing us from putting out the fire that is threatening to burn down our collective house?’ ( Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything, 2014, p18). Klein believes that lowering emissions is in conflict with deregulated capitalism. Averting climate catastrophe ‘is extremely threatening to an elite minority that has a stranglehold over our economy, our political process, and most of our media outlets.’ (p 18). When scientists began to speak seriously about greenhouse emissions, the elite were unfettered, and in 1988 we also became aware of the reality of globalization, the year of big trade agreements. The climate process was struggling and the globalization process was ‘zooming from victory to victory.’ (p19). Market fundamentalism ‘systematically sabotaged our collective response to climate change.’ (p19). The challenges are systemic, politicians and economists have major responsibilities. We all have and our Western lifestyles are critically significant.

The earth is the Lord’s and the Bible has more to say about economics than anything else. Together as people of faith we need to analyse the scientific and social data and bring it into dialogue with biblical and theological ethics, which then becomes a programme of faith in action.

What In The World Are We For?

What responses should Christians together, ecumenical responses, as churches, should we be making to the context in which we find ourselves in Northern Ireland?

Here are three headlines which need to be teased out. Together we need to:

Develop a Public Theology

Public theology is applying theological social ethics to the big public challenges and questions. It is about doing theology in our social, political, economic and environmental context, reading the Bible as a socio–political, economic–eco text alongside our contemporary context.

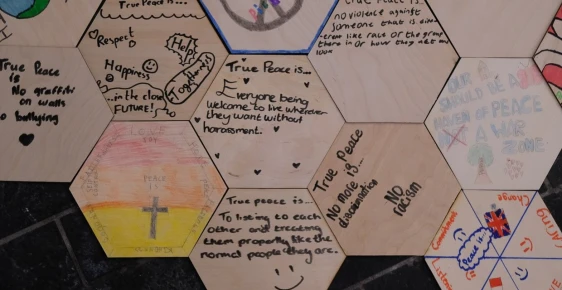

Practice a Neighbourly Ethic

Faith is neighbourly or it is not faith at all. The biblical idea of covenant is the vision and practice of a neighbourly ethic, expressed in radically inclusive justice, tenacious solidarity with all, no exclusions, equality and the creation of a common good.

Nurture a Socially Engaged Spiritually

There is a lot of talk in churches in Northern Ireland about prayer but it urgently needs to become a more socially engaged prayer. This is prayer with the world rather than prayer for it, or for the religious life of the church, or one’s personal life. Every congregation and parish, inter–church group should spend some time in a study of the Prophet Amos whose liberating God is engaged with everyone and not just ancient Israel or Christians. Amos’ core ethic of social justice and righteousness or right relations based on social justice is indispensable. Time also with the Beatitudes, the essence for Jesus of the values and ethics of the Reign of God. And the Lord’s Prayer in its Galilean context and our context, it’s Jubilee vision and practice of release from economic debt and bread enough for all. Amos, the Beatitudes and the Lord’s Prayer are the basis of a socially engaged spirituality.