We gather during the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity to pray for the unity of all believers in Jesus Christ. This is not just a ritual act or a gesture of politeness that we repeat each year. It must reflect a genuine commitment and longing to attain the full visible unity of Christians. This desire is not just about something practical or useful or simply nice. It is the desire to fulfil the prayer of Jesus himself. Today the cooperation between Anglicans, Protestants, Orthodox and Catholic Churches, parishes and communities in preparing for and celebrating the week of prayer has become familiar practice.

We know that it has not always been like this we have all come a long way. This simple fact is in itself strong evidence for the effectiveness of prayer for unity. With confidence, joy and gratitude Christians today can say that “what unites us is much greater than what divides us” (UUS. n. 20, quoting Pope John XXIII).

Just how far we have come is illustrated by a humorous story from about 60 years ago in Alberta, Canada. An Irish Catholic farmer started a practice of bringing his 10 or so Protestant workers weekly to the local café for coffee and a chat. During one of these sessions the men got talking about the plans for building a new Protestant church and their various fundraising activities. Just before they left to head back to the farm the Irish farmer said to the men, you’ll understand lads that as a Catholic I can’t contribute to the building of your new Church, but here’s $40 towards the taking down of the old one!!… That’s a story from about 60 years ago.

Looking back over the last 50 years or so we can clearly see that it has been a fertile period of profound theological ecumenical work, the forging of deep and lasting friendships and openness to the future. What has been achieved has been an extraordinary comfort with one another and that is the area of GRACE, God’s Grace working in individuals and Churches! Gone are the polemics, the uncharitable language, the mistrust from times past. They have been replaced by an authentic desire for prayer together, for theological study, and a desire for friendship. The stated goal of the Council Fathers was nothing less than “full visible communion in faith and in sacramental life, this is the ultimate goal of the ecumenical movement” (UR 8).

But what then are the possibilities for us ever reaching this goal? Are we living in a dream world to think that we can really overcome the essential differences that exist between Christian churches and communities today? Are they not more practical who look for only short–term goals? Where is the ecumenical movement today?

Currently there exists what Dr Rowan Williams terms an ecumenical environment that is somewhat ‘becalmed’. Yes, there has been some real progress but in recent times there is also an increasing commentary of ‘crisis’, a ‘winter’ of ecumenism. Other voices mutter that that ecumenism is now somewhat passé; that the real focus today is on inter–religious dialogue echoing geopolitical shifts.

To say that the ecumenical movement is becalmed or in crisis is not to confess anything necessarily profound or negative. A crisis need not reflect loss of effectiveness. Families facing deep crises often grow closer together and discover the essence of their familial and spiritual resources.

The term ‘crisis’ should not be understood one–sidedly, in the negative sense of a break–down or collapse of what has been built up in the last decades. Here the term ‘crisis’ is meant in the original sense of the Greek term, meaning a situation where things are hanging in the balance, where they are on a knife–edge; indeed, this state can either be positive or negative. Both are possible. A crisis situation is a situation in which old ways come to an end but room for new possibilities open.

Standing back we can broadly identify three strands or elements that will help us understand where we are.

Firstly, I have no doubt that the current situation regarding the ecumenical movement has to be viewed primarily through the prism of spiritual uncertainty that marks much of the West. Ours is a time of unparalleled achievements and capacities, of wealth, technology and knowledge. It is a time marked by global commerce, instant communication and cheap travel, all creating a new interdependence. The paradox of this interdependence is that while it creates seemingly unlimited new links it also intensifies feelings of loneliness and alienation. Everywhere we read signs of crisis of identity in persons and institutions. Uncertainty about who we are, distrust as a result of scandal and poor oversight in the institutions that touch our lives pervades. In such a reality people and churches are not encouraged to search for ways that bind and unite in love. Yet it is precisely at moments such as these that the ecumenical movement finds its greatest reason for its work by reminding and calling the churches to their fundamental mission to become a living sign of communion and hope.

Secondly, in speaking of an ecumenical disappointment Samuel McCrea Cavert writing in The Christian Century argues that the ecumenical movement has become a victim of ‘wild ecumenism’: Those, he says, “who expected ‘instant ecumenicity’ and are discouraged when they do not see it, have little understanding of the ways in which meaningful social advance is made”.

The original enthusiasm of 50 years ago has given way to a new sobriety; questions about ecumenical methods, the achievements of past decades, and doubts about the future, are being expressed. A new generation of ecumenically minded and motivated Christians, especially among the laity, is taking up the torch of the ecumenical movement, but with a different emphasis with respect to its predecessors.

In recent decades we have seen church–dividing issues shift from doctrine to ethical and moral ones. All our churches are struggling to come to terms with issues around human sexuality that are surfacing in our communities. At the heart of these ethical questions is what the President of the Pontifical Council for Christian Unity calls “our image of man; we face the challenge of developing a common ecumenical anthropology, in other words, a doctrine about the human being”. We have entered the era of costly ecumenism.

The goal of unity means we have to struggle together with what it means to be Christian and human in this messy world. Perhaps that conversation within the ecumenical movement has only just begun. We can say that the struggle of the ecumenical movement today is fundamentally a reflection of the challenges of the churches themselves.

Thirdly, may I suggest that the most powerful barriers to unity are often psychological and sociological. Fears around change, fears of loss of identity can lead to inertia or intransigence. Visser’t Hooft, the first General Secretary of the World Council of Churches said: “If we consider our positions, not as fortresses to be defended, but rather as temporary resting–places from which we are to journey onward, we find that other confessions represent truths through which we must let ourselves be questioned, called to order and corrected”.

There is a danger that we, in our various denominations think that we could achieve Christian unity if only the Anglicans were different in such–and–such a way, or if the Methodists didn’t do such–and–such a thing–or, if the Roman Catholics would only…. to put it very simply: if each of the various churches and communions were saying to themselves if everyone else were more like us! Those of you who are old enough to remember the musical My Fair Lady will also remember Professor Higgins’ song: Why can’t a woman be more like a man? We, the audience, know he is being foolish. He would do much better to stop wishing that Eliza Doolittle would behave differently. He really needs to understand why she behaves as she does–which is actually much more reasonable than he supposes. In the same way, it makes a lot more sense that we all learn from other churches than to waste time wishing that they were more like our own denomination.

On the eve of his death, Jesus prayed ‘that they may all be one. As you, Father are in me and I in you, may they also be one in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me” (Jn 17:21). It is significant that Jesus did not primarily express his desire for unity in a teaching or in a commandment to his disciples, but in a prayer, a prayer to his Father. Unity is a gift from above, stemming from and growing toward loving communion with the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Christian prayer for unity is a humble but faithful sharing in the prayer of Jesus, who promised that any prayer in His name would be heard by the Father.

In our work and conversations we should try and keep before us Jesus’s prayer which points to the very heart of a healthy ecumenism: spiritual ecumenism and ecumenical spirituality. This means first of all prayer, for we cannot ‘make’ or organise Church unity; unity is a gift of God’s Spirit, which alone can open hearts to conversion and reconciliation. There is no ecumenism without conversion and renewal, no ecumenism without the purification of memories and without forgiveness.

The 20th Century French priest and ecumenist, Maurice Villlain a pioneer of spiritual ecumenism, said that the first ecumenical action of divided Christians should not be to organise a discussion or pass a resolution but rather “to kneel down together at the foot of the cross of our common Saviour, in a mood of repentance, for we are all sinners before him, we are all guilty in some way or another of the faults of separation.” The theologian Congar put it succinctly when he said: “We can pass through the door of ecumenism only on our knees”.

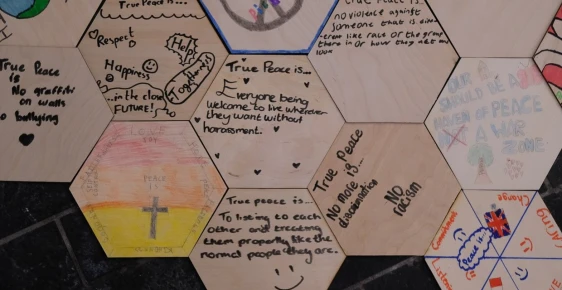

We are Christian by virtue of our Baptism, making a difference in the world is our Christian vocation. Our ecumenical intent is to develop within ourselves a mind a heart for unity. Our journey on the path towards Christian Unity is inevitably also about a common presence in the society in which we live. In this Week of Prayer we are called to reflect on how the Church should be present in the world. St Paul reminds in the second reading that the Spirit of God is at work when the dignity of God’s creation is protected. We are called as Christians to witness together to the possibility of unity in a society which is very much divided. In a society which is marked with anger and violence, we are called to speak out against violence. We are called to cry out together: “You shall not kill”, whether the killings are through gangland–crime, paramilitary violence, or through the evils of the drug trade.

In conclusion, we should not be afraid to fulfil that baptismal vocation in society, even when some may want to limit the space for such a Christian presence. Remember that Jesus promised that he will always be with those he calls his friends (John 15.15): those he calls to himself in baptism and establishes with him as sons and daughters of his eternal Father. And so WE, who share baptism in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, may be confident that Jesus has promised to be with us – to be with the other who shares that baptism. And when we’re tempted to talk of an ‘ecumenical winter’ or ‘crisis’, tempted to focus our attention only on the stresses and challenges between communions of Christian churches, it’s worth remembering that our God is a God who keeps his promise, as he did to the people of Israel, and that he has promised to be with us – all of us – together.