What’s the Story? Lives in Direct Provision

The chief IT engineer of a national university, a marketing executive and a lecturer in fine art … if you talk to people who are in direct provision you never know what you’ll encounter.

Earlier this month I went to an event in Christ Church Cathedral where I met these three people. It was part of the second series of “What’s the Story?” evenings hosted there. These events give us the opportunity to hear the stories of people who are in direct provision.

What really hit me between the eyes was the waste of this system. Waste of money, waste of time, but most of all a waste of talent. Thousands of gifted, eager people forced to sit idle for an indeterminate length of time a “life of restriction” as Stixie, our chief IT engineer dubbed it.

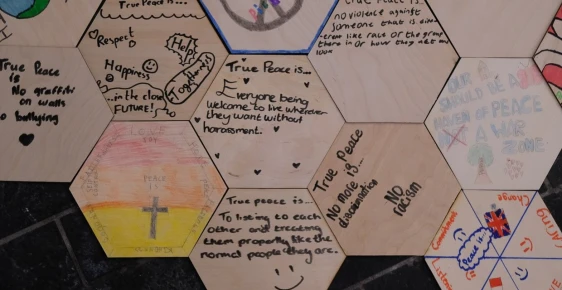

While his skills were wilting on the vine as he tried to keep his morale up by volunteering and doing courses, Joe was painting to guard his mental state. He taught fine art but hadn’t practiced it for a long time. So he spent his €19.10 per week on paper, paint and brushes and now shows and sells his work. He’d love to have a gallery to display his work and to give painting classes to children.

Khalib is a gregarious man whom you can easily imagine working in marketing. He set up his own business and had bought a house by the age of 25. His initiative and energy are contagious.

Whilst the recent initiative to give some asylum seekers the right to work is welcome, it does come with restrictions which mean that none of these people can participate in it and therefore we don’t, as a country, benefit from their passion, skills and drive.

While even such a cost–benefit analysis of the effects of direct provision reveals its failures, as Katie Heffelfinger of the Church of Ireland Theological Institute pointed out afterwards, the stories of these three men show that that kind of analysis is completely inadequate. For the most fundamental failure of direct provision is that it attacks the intrinsic worth of each individual human being, made in the image of God, who goes through it. So as Christians we need to see the face of the other, to hear their stories, and to advocate for the restoration of their dignity and agency so that they can flourish as participants in community and family.

That evening Stixie said that he was not talking to the right people: the people in the room already had opened ears. Therefore we who were sitting there have an obligation to tell the stories to others, to reveal the faces of those we saw, and the stories we heard, so that others can encounter, even indirectly, the person trapped in a “life of restriction” in direct provision. With encounter comes transformed attitudes, and many people with transformed attitudes can push for transformed systems.