Our reading today is not an easy one. Biblical narratives offer drama and story. Psalms offer an array of emotions ranging from delight to despair, and thus can register with our own inner thought life. Proverbs offer wisdom, and many of Jesus’ teachings expound these trajectories of narrative, lament and wisdom. This passage however is slightly different. It jars with modern sensibilities in what it seems to suggest – an exclusion of sorts. The very thing we are lamenting in relation to the housing crisis in Ireland. Who is being separated and why?

Matthew 25: 31–46 – The Sheep and the Goats

“When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, he will sit on his glorious throne. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate the people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. He will put the sheep on his right and the goats on his left.

“Then the King will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.’

“Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you sick or in prison and go to visit you?’

“The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’

“Then he will say to those on his left, ‘Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. For I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me.’

“They also will answer, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or needing clothes or sick or in prison, and did not help you?’

“He will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me.’

“Then they will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life.”

There would be much to note if we were to go through this text exegetically – firstly we would ask if it is indeed a parable, as it is commonly referred to, or if it is an eschatological text, in which case exploring context would be helpful. We could examine first–century Jewish understandings of eternal life, to which this passage refers, and explore how, or if, our reception history (the received way in which we interpret that concept) differs. Indeed exploring any biblical text requires questions. Sandy Eisenberg Sasso recommends that we learn to ‘(read) the Bible with question marks’, allowing conversation with the text to animate our interpretation.

One thing that is clear, is who is notbeing categorised by being put on the right or left – ‘the least of these’. Those who had the capacity to see and act and those who did not are in question here. Those who are in need, society’s most vulnerable, are the linchpin, the key players in the above text. It is the response to those in need, which seems to dictate what way the judgement will roll.

From this we can infer that the very ones who society, ancient and modern, excludes (prisoners, homeless, people with disabilities, outsiders, those who are hungry or for whatever reason do not have the means to provide for themselves) are the ones who exact a standard – from a biblical perspective those who are complicit in their exclusion are the ones who themselves end up experiencing exclusion.

Biblical texts were formed in the social, political and religious matrix of ancient Israel, over millennia. The stories and songs, poems, genealogies, law codes, narratives and wisdom literature reflect within them societal challenges and the responses to those challenges, that were grounded in a moral code which had freedom at its core. Revolutionary ideas, such as caring for the needy, a day of rest for all including animals, and the equal distribution of land might sound commonplace today, but were an anomaly in the ancient world.

The concept of ‘sanctuary’ is one such revolutionary idea. It determines, as we find in the Pentateuchal law codes, a place where those fleeing imminent trial could claim asylum, until a fair trial could be conducted. Across time and culture this concept has been expanded. In Ireland today, the ‘City of Sanctuary’ movement seeks to develop a culture of welcome and inclusion across different communities, identifying vulnerable and minority groups in that process.

One of the chief goals of the Sanctuary movement in Ireland is to stand in direct opposition to a culture of exclusion, most visible in the Celtic Tiger era, which oversaw the development of vast swathes of housing with little or no facilities to accompany them. The net result of this mindless and greedy construction is a fundamental lack of sustainable resources. This immediately sets up the next generation (surely our most precious commodity) for disadvantages that are not limited to geography, but compounded by spiralling unemployment sparked by economic downturns. Migrants, who are often valued only in terms of potential economic contribution, are among the most susceptible to the exclusivist housing policy which has evolved in Ireland.

One key challenge highlighted through this, is a fundamental lack of policy altogether. There IS a housing policy in Ireland, obviously, but it is not strategic or cohesive, insofar as it simply evolved with the demands of a growing nation and economy and is riddled with contradictions. One writer suggests that in the 1950’s and 1960’s the governmental housing policy was actually reasonably effective, with grants and subsidies and social housing which in the beginning was able to meet a growing need. But ‘sticking–plaster’ decisions without a radical revision of our housing policy has enabled, coupled with other complex factors, a housing crisis. Part of the crisis as we know is not a lack of physical housing, it is the type of market which controls it, enabling homelessness among families in Ireland to increase by 232% since 2014, when monthly figures on homeless started being published. Add to this, that almost one third of people in emergency homeless accommodation are children, and we have a system where not only are the most vulnerable excluded from adequate housing due to geographical, social status or employment factors, but most people in Ireland are a mere two steps, or ‘two pay packets’ away from homelessness. Clearly, a re–evaluation of housing policy is desperately needed, one which not only reassesses systematic failure, but recognises the gravitational pull toward exclusion as a model.

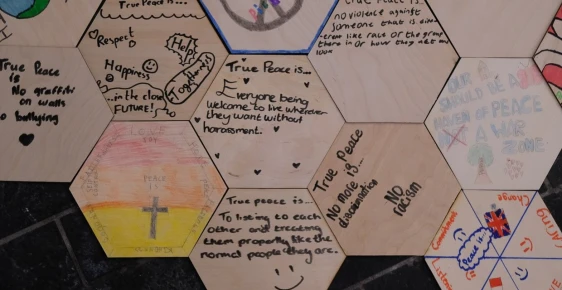

The concept of Sanctuary can therefore be seen as a response to an age–old problem, of complicity and exclusion. Its underlying vision, of creating a culture of welcome which empowers the most vulnerable, fosters a sense of ‘home’ that goes beyond the idea of four walls. A bigger movement, securing a safer future for all and confirming our innate desire to not simply survive but to flourish.

Our opening biblical text strikes a similar chord insofar as it challenges culture structures, which are often built upon systematic exclusion. The only real way for this exclusion to flourish is for people to comply. The sharp picture Jesus paints re–roots his listeners into the rich soil of prophetic principles which ground the biblical texts. It also heightens the idea of incarnation, particularly appropriate during this season of Advent, as his words place him directly in the shoes of the prisoner, the hungry, the weak, the exiled. In first–century Jewish life a confrontation with unjust systems that was weaved from the tapestry of Israel’s sacred stories was not unusual. A voice on the margins was almost expected to draw the people back, and recalibrate personal and systematic orientations toward notions of justice. This Advent, let us all find that point of recalibration, and reconsider assumptions about our own complicity or exclusion, underpinned by the hope which this season brings.

Dr Julie McKinley is Development Officer of the National Bible Society of Ireland.

This post is one of a series on this blog which aims to provide resources for reflection and action on the topic of homelessness. Different voices representing a number of organisations will help focus us on the scale of the issues including the personal and social impact involved. The blog inputs will also offer useful suggestions for study and civic engagement. Small church community gatherings will find them most helpful. There will be seven posts in all and they will be published on every Sunday and Wednesday in Advent. Please pass on the word to others about this initiative. May Advent be a grace–filled time for you. Further resources for churches on housing insecurity and homelessness can be found at irishchurches.org/homeless.